The statements contained in this analysis are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of CMS. The authors assume responsibility for the accuracy and completeness of the information contained in this document.

CMS’ announcement of the redesigned Global and Professional Direct Contracting (GPDC) program, now ACO REACH, created an opportunity for REACH participants to focus on health equity and to finally receive reimbursement payments that are adjusted to their patients’ specific needs. This post is the second part of a two-part series. Now that we understand how ACO REACH benchmarks and health equity adjustments are made, let’s focus on how to “Plan” and “Act” to implement health equity plans that tackle the main drivers of health equity.

CMMI has released preliminary guidance on the Health Equity Plan (HEP). The official PY2023 HEP will be due no later than March 31, 2023, which will be after REACH ACOs receive their PY2023 aligned beneficiary populations, to best identify and address disparities in their respective communities. CMMI has also created an opportunity to receive feedback on their proposed HEP in advance of the mandatory submission in March 2023. The optional preliminary HEP is due to CMS by September 16, 2022. More information on the preliminary submission can be found on CMS’ website.

A multidisciplinary workgroup is a great starting point for health equity intervention planning. Based on clinical quality frameworks pioneered by the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) as well as Lean methodology, this blog post will outline a process that can be considered best practice to establish and execute a health equity initiative at your organization.

Planning

The health equity planning process warrants the formation of a work group or committee, a governance structure for that committee, and a process to keep committee members accountable for not only planning but also executing on the health equity plan. Other key requirements for the committee:

- The committee should also be supported by executive leadership, including time and budgetary allowances necessary to execute a health equity plan for the organization. Ideally, the leader of the committee will report directly to a member of the C-suite or senior leadership.

- The committee should be multidisciplinary, with representation from departments within the organization that are involved in both caring for patients as well as leaders from operations, administration, and in some cases, community-focused departments. This blog post is written assuming that the broader organizational leadership has ’bought in’ to improving health inequity for their patients. Below is an example of the necessary committee members to compose and execute a health equity plan for an ambulatory primary care provider:

VP or Director, Population Health (‘Chair’ or committee leader) | |

VP or Director, Administration and/or Operations | |

VP or Director, Nursing | |

VP or Director, Clinical & Quality Leader | |

VP or Director, Case Management | |

Data analysts, EHR experts | |

Project manager |

Accountability within the health equity planning committee is integral to ensuring that the plan is written and executed. Collaboratively establishing the committee’s goals, guiding principles, timeline, and specific roles and responsibilities during the kick-off allows input from the broader committee, creating a foundation for accountability among the team. Our favorite saying fits well here, ‘garbage in, garbage out.’ If the building blocks of forming the health equity plan are insufficient, then the health equity plan and its interventions will not help one’s patients and produce more equitable care.

Understanding The Drivers of Health Inequity in Your Patient Community

A health equity plan must be data-driven and tailored to the unique needs of one’s community. Though health equity plans across various organizations may look similar, each organization must ensure that their strategies to bridge health inequities are sensitive and specific to their population. ACO REACH requires not only the submission of a health equity plan but also performance under that plan by the ACO. To this end, data analysis of existing clinical and demographic data, and in some cases new data collection, must be the first step in the health equity planning process. Without measurable metrics as part of the health equity plan, the ACO will not be able to demonstrate improvements. Depending on the type of data that your organization has been collecting historically, it may also be helpful to work with local community-based organizations that can help identify drivers of health inequity (e.g., food insecurity, housing insecurity, access to care, access to pharmacy, etc.). The self-reported data required by the ACO REACH program is a good starting point.

The data analysts and EHR specialists on the committee will be crucial for this aspect of the planning process, as they are most familiar with the data. A literature review of peer-reviewed articles related to population health drivers, specifically studies that have similar populations to your patients, are also helpful guides to understand how to create analysis frameworks1,2. An organization may consider conducting a formal community needs assessment3, which many provider organizations publicly report periodically. The population health leader on the committee will determine if a formal community needs assessment is necessary, and further administrative and budgetary support from the broader organization may be required.

Identifying health inequities can be a daunting task as there are many factors that can be considered. Mutable vs. immutable factors is a distinction that is seen in many academic papers:

- ‘Immutable’ factors: race and dual eligible status (patients who are simultaneously eligible for Medicare and Medicaid)

- ‘Mutable’ factors: examples include food insecurity, lack of transportation, and other social determinants of health

For many organizations, however, data exploration will need to begin with the data that they have available to them. Most organizations have not yet collected sufficient data on the mutable factors to analyze their entire population.

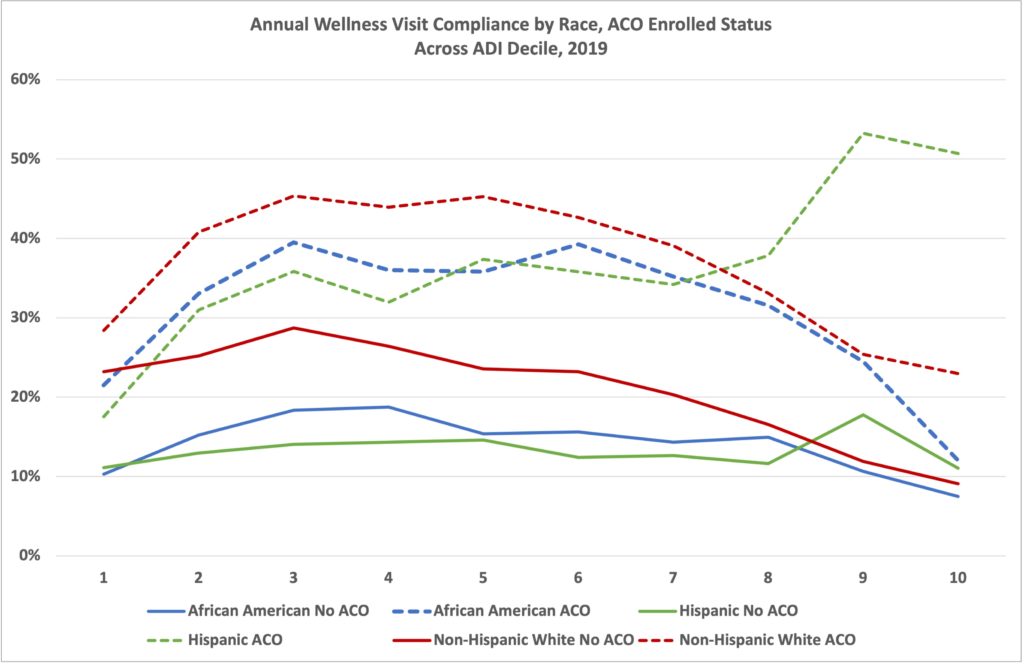

Most organizations are likely able to evaluate their populations along gender, race, age, geographic location, and Dual Eligibility axes. From these evaluations, organizations can dig deeper into why disparities exist within their organization and create action plans and goals around how to effectuate change. As an example, we looked at a simple preventive metric – Medicare Annual Wellness Visits (AWVs). This was broken down into:

- Race

- Dual-eligibility status

- Area Deprivation Index of the county in which the beneficiary resides

- Whether or not they are part of an Accountable Care Organization

- Note: We are only displaying African American, Hispanic, and White populations because each population represents over 10% of the population and the graphs get visually complex with additional data sets, but we are acutely aware of disparities also existing in the Asian/Pacific Islander population and especially the Alaskan-Native American populations

Implementing Actionable Health Equity Interventions Based on Data

According to CMMI, the data sources that could be used to identify disparities include but are not limited to: Census data, community health needs assessment data, the Mapping Medicare Disparities Tool4, ICD 10 codes, Z codes, data from the National Quality Forum (NQF), and quality data from Hospital Compare. Additional data sources could include metrics related to demographics, income, location of their home and workplace, distance and access to necessary medical and social services, clinical outcomes, social outcomes, social support, and external factors. The conclusions from the analysis should be actionable, and interventions should be focused on the areas that have the greatest impact or opportunity for improvement. Statistical analysis need not be performed, but instead, decisions based on quantitative representations of qualitative observations will lead the charge. For example, if 80% of patients live more than three miles from the nearest pharmacy, this could indicate a barrier to medication adherence and chronic condition management. An actionable solution would be to work with a local pharmacy to create a mail or courier delivery system for these patients. In this instance, surplus created from REACH capitated payments could be used to cover the expenses related to this type of service, as increased medication adherence would likely lead to improve clinical outcomes and less utilization of high-cost avoidable medical services. In the clinical quality world, researchers and clinicians use the “Plan, Do, Study, Act” cycle methodology5. First, plan a small pilot of an intervention on a small subset of patients. Then do the intervention, collecting data in the process. Then, study (or analyze) the data and the process that was created. Usually, a process needs to be iterated a few times before the kinks are ironed out. Making incremental changes to the intervention and process can occur as many times as needed to get the intervention right, that iterative process is the act. Once the most effective process is refined and the data collected during the pilots point to improvements in process and outcome measures6, then the pilot can move into the implementation phase. The PDSA process is illustrated below, using the prior example of mail-order pharmacy. Please note that PDSA cycles are just that: cycles. Thus, three cycles are described below.| Plan | Identify group of 10 patients to enroll in the pilot mail order pharmacy program. Criteria for enrollment: medication adherence is a challenge, patient lives more than 3 miles from pharmacy, patient is willing to receiving medications from the pharmacy via mail. |

| Do | Plan Cycle 1: Send each patient their medications as needed via mail Plan Cycle 2: Send each patient their entire medication regime, each medication in separate bottles, twice a month Plan Cycle 3: Send each patient their medication once per month, and medications are sorted for the patient in pill pouches marked for day of the week and time of day (e.g. Monday morning pouch, Monday evening pouch, etc.) |

| Study | Study Cycle 1: collect data on patient medication adherence based on self-reported survey via mail-in questionnaire Study Cycle 2: collect self-reported medication adherence data via SMS text message once per month Study Cycle 3: collect self-reported medication adherence data via SMS text message once per day, in the evening after evening medications |

| Act | Implement mail-delivery pharmacy for patients who have difficulty accessing a pharmacy. Send each patient their medication once per month, and medications are sorted for the patient in pill pouches marked for day of the week and time of day. Collect medication adherence data at annual check-ups, and any interim doctor visits as needed. |

Implementing Interventions to Address Health Inequity

Once a set of interventions are identified as successful in the pilot phases, the processes to implement the intervention must be codified in writing by the committee and communicated effectively to the frontline staff who will be responsible for guiding patients through each intervention. Trainings with all frontline staff involved in each intervention will be necessary to ensure that roles and responsibilities, troubleshooting strategies, and escalation pathways are established. Depending on the intervention, a workflow may need to be built into the EHR or other software that is used to manage patients. Regardless of the way that an intervention is codified, it is crucial to ensure that there is a working document outlining granular details of each intervention is made available as a reference to staff. Population health leadership should also be available as a resource for frontline staff who are managing patients in new health equity interventions. No matter how many pilots were successful, difficult situations will arise in each intervention and will identify opportunities to continue to refine the new process. As alluded to in the previous section, it’s important to focus interventions on the subsets of populations that require these types of services. The mail-order pharmacy example may not be helpful for a beneficiary that lives next door to a pharmacy but has obstacles to health in another capacity, like being far from the clinic or needing a translator when speaking to the provider. Stratification of populations is necessary to ensure that the right interventions are being delivered to those who need that specific intervention. Though stratification is necessary, it’s also necessary to account for the possibility that the same beneficiary may need more than one intervention. To ensure that patients are receiving the right interventions, assess health equity drivers at various touch points, such as during routine visits or when patients interact with reception staff via phone or text message. Finally, and most importantly, measure the impact of all the interventions set forth in the health equity plan. Collect data periodically and review each intervention with the health equity committee periodically, quarterly, or bi-annually if not more frequently. A culture of ‘continuous improvement’7is necessary to ensure that health equity plans persist, and that they stay top-of-mind for your busy organization. Transparency around both successes and failures will lead to more effective interventions, what might have worked very well last year may not be having much of an impact this year. Feedback from frontline staff that are leading the intervention with beneficiaries should be welcomed and acted upon, and ineffective processes must be addressed expediently. The key is to catch when outcomes from interventions are not improving, and to either tailor the intervention or to create a new one. The goal is to address the main drivers of health inequity, not for interventions to run indefinitely if unsuccessful. Though health equity planning may seem like an insurmountable task, convening a collaborative, multi-disciplinary, data-driven group of leaders and a culture of transparency and continuous improvement will lead your organization to an effective strategy to address socioeconomic factors which are contributing to health inequity. The process outlined in this blog post can be replicated to facilitate not only health equity planning, but also other clinical and social initiatives that could improve the health of your REACH beneficiaries leveraging surplus premium. The health equity plan requirement in ACO REACH is an opportunity to finally unlock all the data a healthcare organization has been collecting, and to act in a way that improves the health, and hopefully lives, of the community.About CareJourney

CareJourney was founded in 2014 under the belief that our nation’s transition to value-based care is an important one, but without an “operating manual” that can reliably deliver on the promise of better quality at a lower cost. Our mission is to empower individuals and organizations they trust with open, clinically relevant analytics and insights in the pursuit of the optimal healthcare journey. To learn more about CareJourney, please visit www.carejourney.com. References- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. (2015, July). Types of Health Care Quality Measures. Retrieved from Agency for Healthcare Quality and Research: https://www.ahrq.gov/talkingquality/measures/types.html

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. (2020, September). Health Literacy Universal Precautions Toolkit, 2nd Edition. Retrieved from AHRQ.gov: https://www.ahrq.gov/health-literacy/improve/precautions/tool2b.html

- National Quality Forum. (2017). A Roadmap for Promoting Health Equity and Eliminating Disparities: The Four I’s for Health Equity.

- Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation. (2021). Developing Health Equity Measures. HHS.

- Wyatt R, Laderman M, Botwinick L, Mate K, Whittington J. (2016). Achieving Health Equity: A Guide for Health Care Organizations. Retrieved from Institute for Healthcare Improvement: https://www.ihi.org/resources/Pages/IHIWhitePapers/Achieving-Health-Equity.aspx

- CMS. (2022, July 29). Preliminary Health Equity Plan Template. Retrieved from Centers of Medicaid & Medicare Services.

- CMS. (2022, July 29). Preliminary Health Equity Plan FAQ. Retrieved from Centers of Medicaid & Medicare Services.